March 13th, 2021Corruption, intrigue and damn delays and danger

WITH the Victorian gold rush of the 1850s, came the realisation of just how vulnerable the growing settlements were to unsanitary water. The few creeks that ran through Castlemaine to Bendigo flowed well in winter but were reduced to fetid ponds in the summer.

Outbreaks of cholera and typhoid were common with a death rate for infants at around 220 for every 1000 births. The need for a reliable and clean water supply was undeniable.

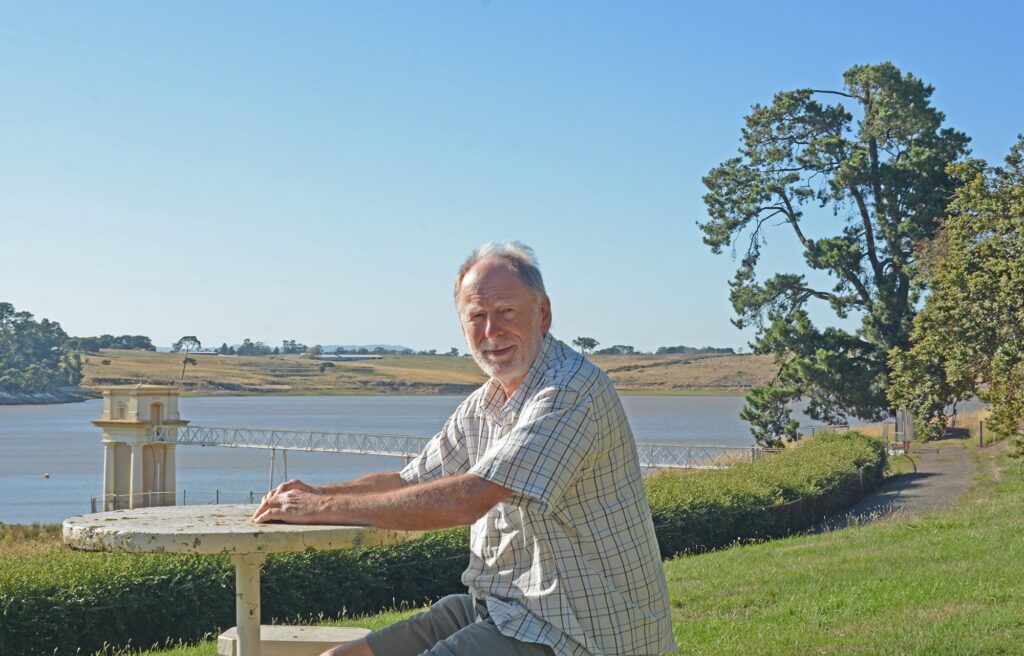

In 1862 the Victorian Government offered a prize of 500 pounds for a suitable design of a drinking water reservoir on the Coliban River just south of Malmsbury. It set in motion an industrial saga replete with all the corruption, delays, intrigues and danger befitting a grand engineering project of the Victorian age. Enough to even fill a book, and that’s what Malmsbury resident Rod Andrew did, he put a book together on the subject – Malmsbury Reservoir: A History in News Articles and Pictures.

“I first heard about (the Malmsbury Reservoir) back in the 1970s,” says Rod. “I worked for the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission, the predecessors to Coliban Water. There were many stories going around about the Coliban water system and the Malmsbury Reservoir had a bit of a name. It was mainly bad from the engineers’ point of view because they had a lot of trouble with it.”

Today there are two additional sites along the river that opens out from its headwaters at Trentham. These include the Upper Coliban Reservoir near Tylden completed in 1903 and Lauriston Reservoir completed in 1941. Together they make up the Coliban Water Works. The winning design (titled Progress) was presented by Joseph Brady, the chief engineer at the Bendigo Water Works Co (later absorbed into the Department of Victorian Water Supply).

Mr Brady was capable and respected, and the construction project may have run smoothly under his guidance but he departed to Queensland to manage other projects before construction commenced. Ultimately charge of the project fell to one Henry Christofferson, the newly minted chief engineer of water supply. Contractor Thomas Greenwood was employed to commence building the wall in 1866. Construction was fairly straightforward, featuring an earthen embankment with a puddle clay core (packed clay to prevent leaks) and washes at either end to pass floods.

But as it was, the construction was beset by delays and recriminations which saw a 15-month build stretch to seven years not helped by the inexperience of Christofferson.

But bad engineering and catastrophic failures were very much a part of the spirit of the age. Engineers were often hired on experience, not necessarily actual qualifications. This led to spectacular disasters such as the 1864 collapse of the Dale Dyke Dam in Yorkshire, England which drowned 240 people. Such events weighed heavily on the Victorian Government during planning, and the Malmsbury Reservoir came very close to joining that ignominious list.

“Christofferson specified building materials that should not have been used, didn’t supervise the work and there was corruption at every level,” says Rod. “He was eventually sacked along with two other resident engineers who were charged with concealing faults in the construction. It was a sign of the times that Christofferson had the role at all but he was well connected and had friends in parliament.”

The year 1870 saw a lot of rain in Victoria and the newly completed reservoir was full to overflowing which quickly revealed its poor construction. By July leaks had appeared with some described by the Kyneton Guardian as: “Strong jets as if thrown by a powerful syringe.”

Christofferson remained sanguine stating: “The percolation of water was trifling.” However by September The Argus wrote: “It must be evident that, with such a rush of water, the destruction of the embankment at this point is but a matter of time.”

History notes no flood of biblical proportions sweeping away the village of Malmsbury. The leaks (caused by a poorly constructed outlet pipe beneath the embankment) were addressed.

Embarrassingly it required the Victorian Government to bring in engineering expertise from the then British colony of India to effect solutions. That came in the form of Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Hieram Sankey of the Royal Engineers. Another imported expert, one G. Gordon, then rectified the worst defects as Sankey found them. The result being a reservoir that remains in operation to this day, 155 years after the turning of the first sod.

Thanks to Rod Andrew, author of Malmsbury Reservoir: A History in News Articles and Pictures for his assistance with this article.

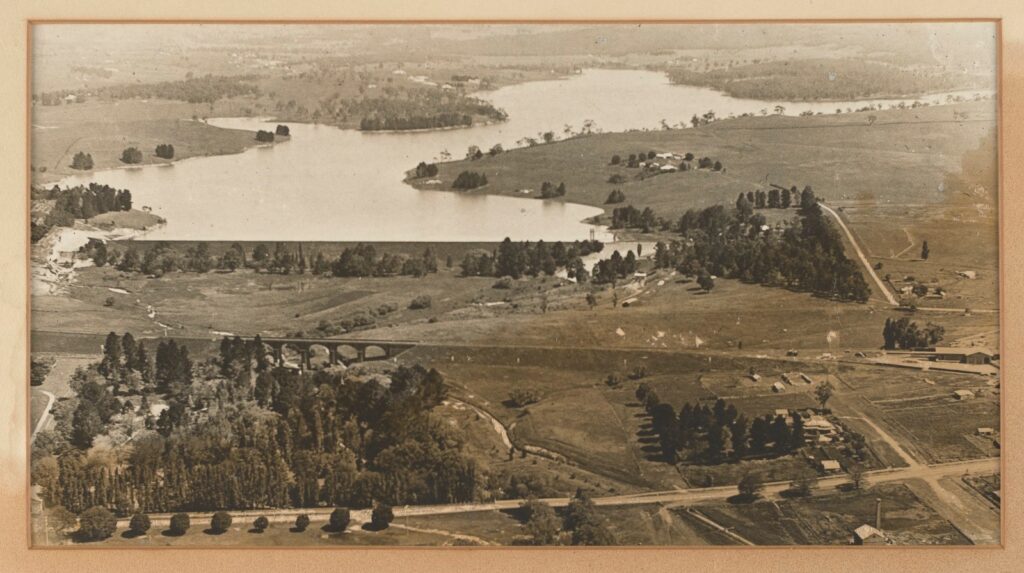

Above, an aerial view Malmsbury Reservoir with the village in the foreground from 1931 | Image: State Library of Victoria

Below, Rod Andrew | Image: Tony Sawrey

Words: Tony Sawrey