April 13th, 2022From convict to land holder

ON THE river flats along Creswick Creek in the area known today as the township of Clunes, European settlement emerged to take advantage of the land for the growing of livestock.

And before the 1850s life was, for the handful of pastoralists scattered across the area, a relatively peaceful one dictated only by the weather and shift of the seasons. The discovery of gold in 1851 changed all that forever.

As historian Robert Hughes succinctly put it in his 1987 book The Fatal Shore: “Gold disturbed the order of Anglo-Australian society — from pastoral “aristocrat” down to convict — with shudders of democracy.”

With gold came a fresh influx of people from across the seas, not just those compelled to be here as punishment. While many came to feverishly pursue a metal described by the London Times in 1852 as the “yellow stuff”, others carved out prosperous careers servicing the needs of the exploding mining economy and development it facilitated.

“Gold wealth was not democratic,” Hughes writes, “but it did expand the existing oligarchy…and help create the Australian bourgeoisie.”

One of these people was Henry (Harry) Robins. He was born poor in 1827 growing up in Northamptonshire. At 17 years of age, he was convicted of ‘Robbery with Violence’ and transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) for 15 years.

However, Robins must have demonstrated some potential for reform as he was granted a conditional pardon and ticket of leave after just two years. By the end of the 1840s he had added an extra ‘b’ to his surname and set out for the colony of Port Phillip.

The tiny colony on the southern coast of the Australian mainland was still a part of New South Wales. However, its small Anglo population, hobbled by the impracticalities of administration by far-off Sydney would soon form the new state of Victoria with Melbourne as its capital. Robbins soon found employment as an agricultural labourer in and around the district of Clunes station, a 32,000-acre (13,000-hectares) property held by Scottish businessman Donald Cameron.

At the same time the state of Victoria was formed, the discovery of payable gold was announced, despite the best efforts of pastoralists to keep the news out of the papers.

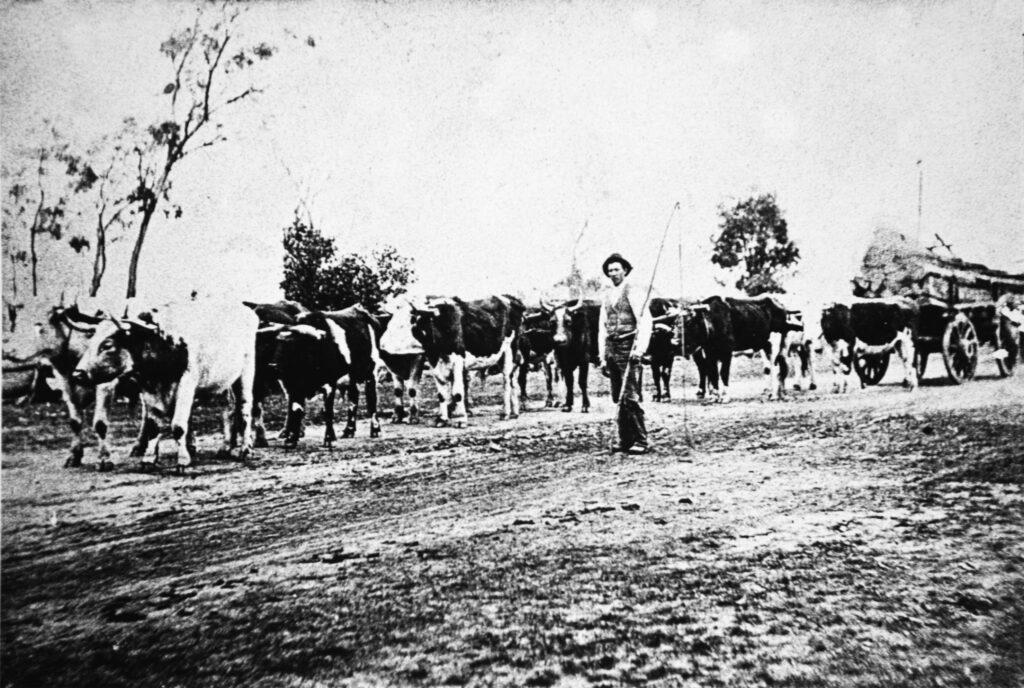

By 1851 thousands of people were pouring into central Victoria and for men like Harry Robbins the booming mining economy was a chance to make something of themselves. His own road to prosperity came not by swinging a pick but establishing himself as a bullock driver and he is believed to have transported the first shipment of gold quartz from Clunes to Ballarat.

Some may say it was akin to leaving a fox in charge of the chook shed for an ex-convict to be tasked with moving a shipment of gold but it appears that Robbins may have successfully obscured his convict past.

According to one recent community contribution on the Australian Convict Records website: “It was firmly believed by his descendants that he ran away from home, jumped on a ship to Van Diemen’s Land, deserted it while docked in Melbourne and joined the gold rush.”

By 1853 he had married one Elizabeth Macintosh at the Clunes station homestead and they went on to have 10 children with several descendants remaining in the Clunes district to this day. By the 1860s Robbins had bought land at Glendaruel and Tourello before finally moving to a farm at St Arnaud where he died in 1899.

The story of Harry Robbins is a modest one but familiar to anyone who has delved into the social history of European Australia and the development of 19th century Victoria. In England, Robbins would have had little chance for advancement.

But transportation along with the economic opportunities brought about by the Victorian gold rush allowed him to turn his life around from that of a convicted robber to a prosperous farmer. He succeeded in living a life far beyond the station that would have been allocated him back in the old country.

Thanks to Allison Thorpe and the Clunes Museum for their assistance with this article.

Above, Harry Robbins with his bullock team on the Clunes Road 1860s.

Words: Tony Sawrey