May 4th, 2024Glen, about the house

Movement in the garden

I’m sure I’m not the only one who makes a daily tour of our newly planted trees or shrubs, looking anxiously for any sign of new growth.

We all know, of course, that any new outward or upward growth, except in a few ‘Jack-and the beanstalk’ plants, and a few vines, can be too slow to be considered as movement at all – unless you live in Far North Australia or in the tropics. But, as always, there are a few exceptions.

Some plants have a regular cycle for opening their blossoms each day to attract with their fragrance, bees and other winged pollinators, but closing again at dusk to evade the scavengers.

Many other more miserly plants such as some iris only open for business for just one day before closing forever – apparently preferring the ‘fast trade’.

Others open at certain times of the day in order to attract particular patrons. These include the four o’clocks (mirabilis jalapa) which true to its name, opens at the same hour and stays open all night. ‘Morning Glories’, like a few others, open at first light and close again at noon.

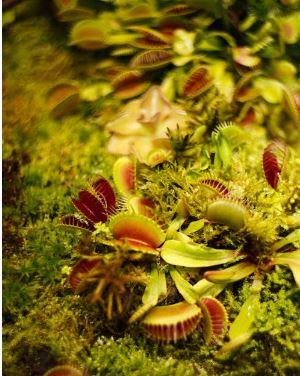

Many other more bloodthirsty plants are the insect trappers where you will see definite and fairly rapid movement, such plants as the venus fly trap (dionaea muscipula), a perennial herb from the swamps of North and South Carolina.

At the base of each 30cm long stem that produces white flowers, we will find a rosette of leaves consisting of two parts with a hinge between them.

Whenever an insect alights on a hairy leaf, the two parts of the leaf snap close to enfold the insect until it dies and its body juices are absorbed. The leaf closes within half a second after the insect touches it.

Twining

Twining vines present an amazing, although rather slow movement, with some twisting from left to right, while others prefer to twist from right to left.

No matter what you do in an attempt to reverse the natural direction of the twisting/twining the plant will persist in twisting around its support, but only in its own predetermined direction. This spiral twisting of a plant stem is called nutation.

Our good old garden friend, the sunflower, turns so that its large, flat blossom is at right angles to the sun. When each flower reaches maturity and its stem has become hard and stiff, no more movement is possible, but when it’s in bud it follows the sun across the heavens.

We can also see extremely fast movements in the method some plants use in dispersing their seeds. When a ripened balsam’s seed pod is touched, it seems to explode as the outer casing breaks into sections and curls back, sending the seeds flying in every direction over a wide area.

In late summer, violets develop pods that break open in three sections and send a great many seeds as far as one to two metres – and it seems that every one germinates, as we have found to our delight in the few years since we moved to our current garden.

But the king of rapid plant movement is the sensitive plant – mimosa pudica – which has entertained children and amazed adults for ages. The stems are spiny and the leaves are cut into many leaflets. Just the lightest of taps causes them to fold together – a heavier tap and the stem will droop down. A few minutes later they will resume their normal positions.

And finally, there are many other plants that close down for the night to reawaken in the morning sun’s light in what is called a sleep movement.

Got a gardening query? Email glenzgarden@gmail.com