May 24th, 2022Not so much a Victorian gold rush, a job rush

THE great Central Victorian gold rush brought thousands of people to the region. Today most people imagine men humping swags and tools ready to scratch away at the earth in a fevered hope of finding something to secure their fortune.

It is a somewhat inaccurate representation of what gold mining actually required. Alluvial digging, carried out by individuals and small groups working in shallow shafts, had mostly disappeared by the end of the 1850s.

In later years, large syndicates took over the work and gold mining evolved into massive industrial operations, including plunging shafts over 200 metres through layers of basalt chasing the courses of ancient gold-filled riverbeds that had not seen the light of day for several million years. One of the richest areas was the area north of Creswick known today as the Buried Rivers of Gold region.

“The area has some of the best preserved gold rush landscape anywhere,” says Margaret Giles, secretary of the Creswick Business and Tourism Association. “The mullock heaps, mining relics and tiny miners cottages are still here to tell the story.”

It is a story the association wishes to keep alive. With support from Hepburn Shire Council, Heritage Victoria, Creswick and District Community Bank, RACV Goldfields Resort and others, they are in the process of renewing signage identifying the many sites along with a new website and guides for self-driving tours.

Once the installation of new markers is complete they hope to officially launch the revitalised trail later on this year.

From the 1870s until the turn of the 20th century dozens of mines were built there, requiring vast reserves of manpower to operate them. And for the thousands of workers who flocked to the area answering the call, this was not a gold rush, it was a job rush; brought about not by some irrational tilt at instant riches but just the chance of a decent steady income.

All the true irrational impulses lay with the numerous investors financing the developments. From as far away as the United Kingdom, they poured money into numerous start-up companies and dozens of operations.

A huge amount of capital was required for the manufacture and installation of machinery and the development of the sites. Speculation was rife, some mines paid off handsomely, others produced nothing or were defeated by rising water and deadly gases.

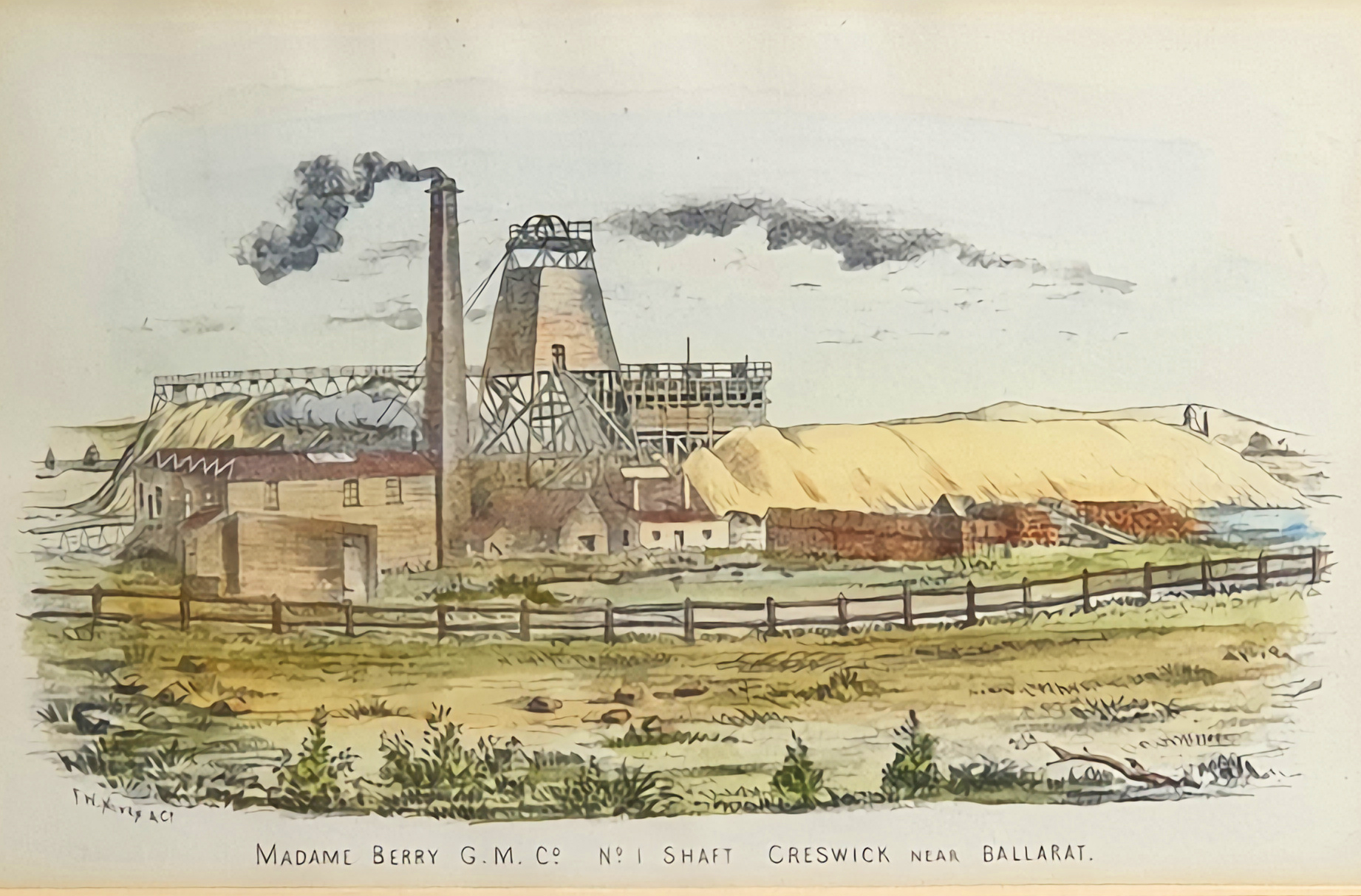

Of all these operations the most successful mine was Madame Berry No 1 securing over 10,000 kilograms of gold from its tunnels. Others, such as Berry No 1 mine further north, despite the installation of a 10-tonne pump withdrawing up to 270,000 litres of water an hour, were destined to fail. Millions of pounds were made, millions of pounds lost with little more than mullock heaps remaining to show for all that effort.

Today’s Buried Rivers of Gold route begins north of Creswick at the New Australasian No 2 mine. This was the site of Australia’s worst mine disaster in 1882 when 22 miners drowned. From there, the trail heads 10 kilometres north to Berry No 1, back east towards Smeaton before turning south and passing through the remnants of old mining villages such as Allendale, Broomfield and Smokeytown before returning to Creswick.

In all there are around 100 waypoints on the drive comprising a substantial portion of the UNESCO World Heritage bid to recognise the historical Central Victorian goldfields region.

“The plan to submit a World Heritage bid demonstrates that the areas have a connection to the past that has deep meaning for the local community.” says Margaret. “But the bid process will take time and meanwhile local sites such as the Buried Rivers of Gold region continue to need protection and that’s what we are doing.”

Words: Tony Sawrey

Main image: Madame Berry GMC No 1 shaft 1887 lithograph, courtesy Victorian Collections | Bottom image: Berry No 1 mine ruins, Tony Sawrey