May 4th, 2022Making tracks: the timeless history of our trees

WHO would guess that to some people big storms and bushfires are almost welcome? The measured pleasure they get is because these disasters may laying bare secrets tucked away in the bush, such as century old timber-getting tramways in the Wombat state forest.

Nature’s archaeologists helped uncover some of the tramways that stretched for about the same distance as the return journey from Daylesford to Ballarat. Their hiding places and burial spots are being recorded by researchers such as historian Norman Houghton and local enthusiast David Endacott.

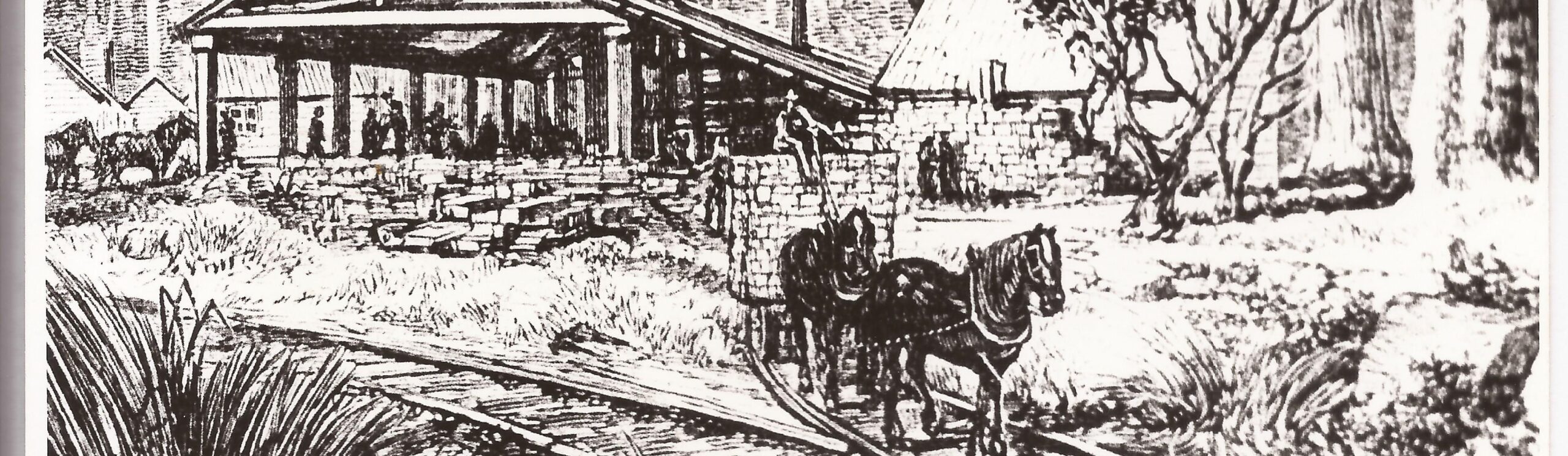

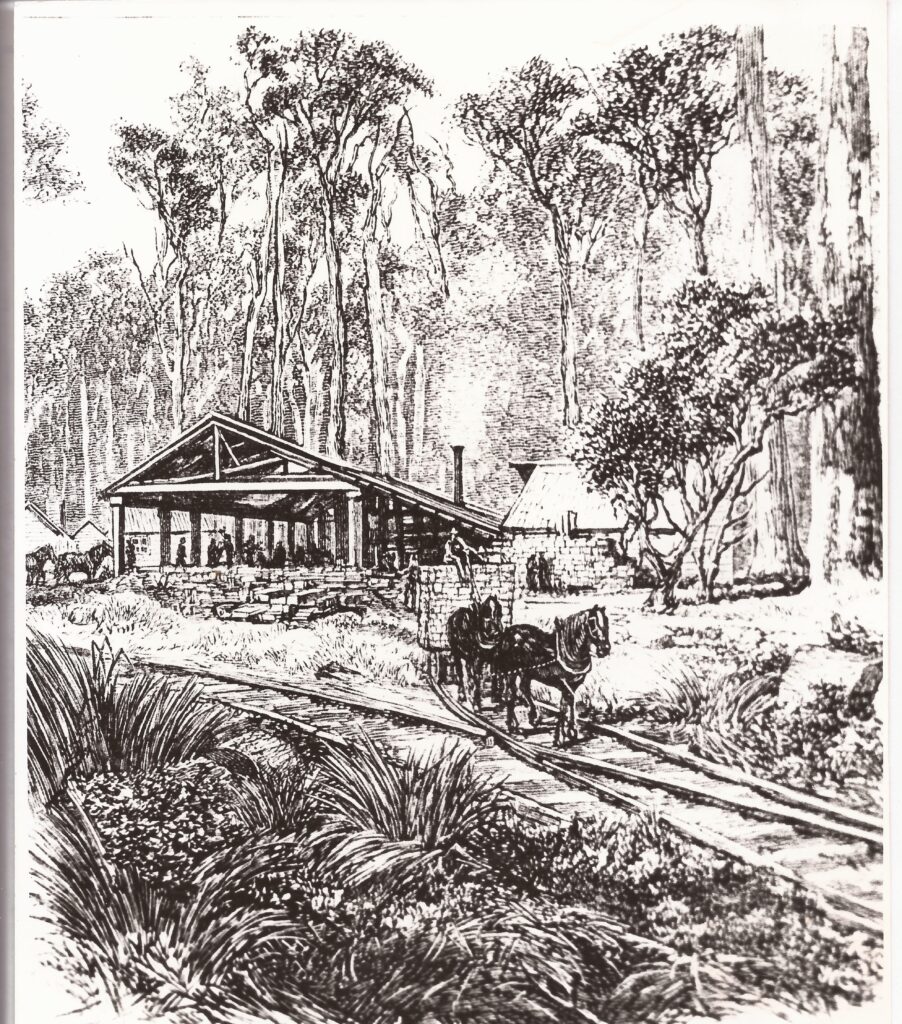

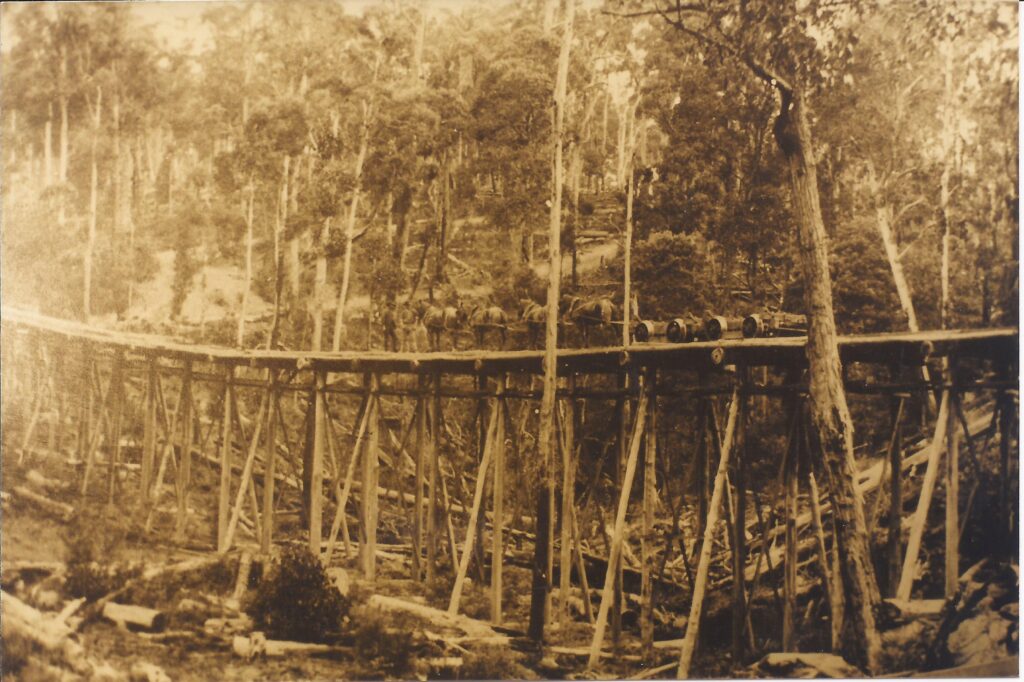

Surprisingly, the first primitive sawmills began not long after gold was found in 1851. Sturdy horses pulled loads of logs along a spider’s web of tramlines to mills and then to market.

Within four years, as the gold rush roared on, deeper and more complex mines were needed, so hewn and split timber was called for to line shafts, fire boilers, provide sleepers and more. This meant felling masses of trees with axe and saw, including a giant at Dean with a 11.2-metre circumference at the bottom, tapering to five metres at the top.

To show some of the evidence of those hectic times, Houghton and Endacott take The Local from Bullarto four kilometres along a maze of tracks where they enthusiastically point out an apparently rare sight of two tracks joining. Nearby, more tracks sunk in the scrub lead to the Lerderderg River.

Proof of a link from the road to Glenlyon to the river is offered by a long, hollowed gully.

“Magnificent,” says 73-year-old Houghton, who has written a history book a year since 1974, a total of 42 books. He is praising the dank and sodden undergrowth, which reveals more clues as the sun breaks through.

A cutting slopes down, banking sharply into Sardine Creek, which bubbles down to the Lerderderg River. So down we go to a massive fallen tree, a victim of the tremendous storm in June last year that revealed so much. Astonishingly, we also come across 120-year-old timber tracks still intact.

We find out about James Henry Wheeler, a big operator whose Sardine Mill on Wild Dog Creek ran a tramline to the Bullarto South, Coliban and Kangaroo lines. Wild Dog Creek was known for its steepness, but until the storm was hidden in impenetrable two metre high wiregrass. This was a find by 76-year-old Endacott, whose other specialty is handmade tools.

Wheeler started sawmilling near Vaughan Springs about 1854, then moved to Porcupine Ridge and on into the Wombat state rorest. His self-promotion would be unlikely to be celebrated today: elected to the state parliament in 1864, he resigned three years later but was back for a further 20 years in 1880. Becoming Minister for Railways, he was able to ensure his timber got to market.

Timber-getting in the bush had its dangers. Houghton, of Geelong, who received the Order of Australia for his histories, tells of an engine driver who kept putting on fuel to get up steam, not noticing a pipe connected to the boiler had been blown out of place. Just in time he saw there was no water in a glass indicator and extinguished the fire.

A young boy, whose job was to remove sawdust from the staging where the timber was cut, became entangled in a shaft revolving 160 times per minute. It whirled him around 20 or 30 times, threatening to obliterate him, before the engine could be stopped. One of his arms was broken in two places.

Reflecting on this powerful history we have a last moving moment at the end of our tour. Towering 16 metres or more above us, rifle barrel straight, is a 130-year-old messmate gum. It is smack in the middle of a once well-used tramline, a living monument to that moment when it all ended.

Words: Kevin Childs | Images: Kyle Barnes / contributed